Seeing Our Parents Home

Though we hope that death comes quietly to beckon our parents home, reality is often bracingly different. Not long after my father turned 80, he was diagnosed with prostate cancer. COPD had already taken a toll, limiting him to approximately 15 minutes of physical activity at a stretch. Hoping to beat the cancer, he reluctantly agreed to radiation and hormone treatments.

It was humorous to commiserate with my father about hot flashes. Whenever we talked on the phone, he asked, “How do you deal with them? They’re so awful!” At that point, he had no idea the hot flashes would be the least of his problems.

New Territory

My husband and I are among the 20 million adults in the sandwich generation: simultaneously parenting our own children and caring for aging parents. We’re signing permission slips for our teenager’s field trips alongside do not resuscitate (DNR) orders for our parents.

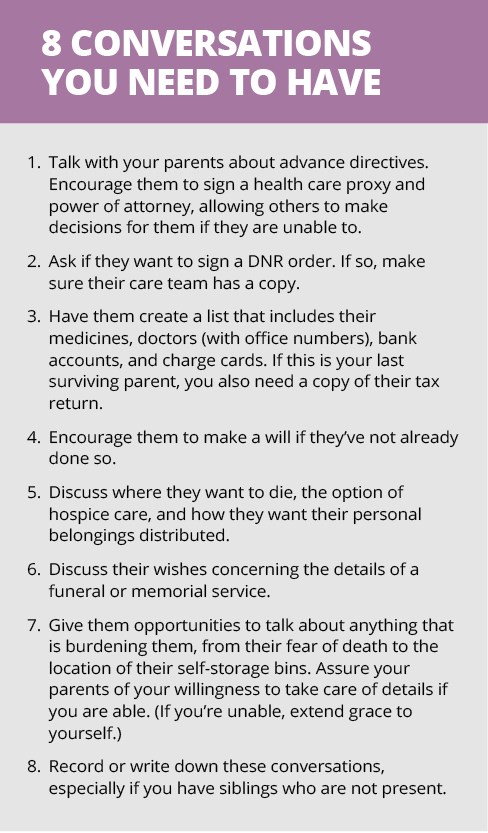

Few of us are prepared for the physical, spiritual, and emotional challenges of this season. Too often, we defer to health care professionals to decide what’s best for our parents. But a doctor who has not previously met them may not know what’s best. That’s why we need to have candid conversations with our mothers and fathers about the end of their lives—before a crisis hits.

After my father was diagnosed with cancer, he was willing to talk about the practical aspects of his final years, including his health care plan and how to pare down his belongings. Above all else, he wanted to finish life in his home, where he lived for almost 60 years.

Unlike my father, some parents resist having such conversations and possibly even resent offers of help. End-of-life discussions force us to face our mortality and reckon with our impending losses—things that we generally prefer to avoid.

Additionally, our parents may want to retain control of their lives as long as possible. Though their resistance may be frustrating, we need to extend patience and grace. In such situations, a gradual approach may work better. Give them time to prepare by asking if they would be willing to have a conversation at some point. If they decline, try again in a few months.

An Unexpected Detour

During the last week of my dad’s radiation therapy, he fell, shattering his hip. I got the call moments before a speaking engagement. After a forgettable presentation, I rushed home, packed my bag, and drove five hours to his hospital.

Twenty-four hours after surgery, his kidneys started shutting down and he developed sepsis. For three days, it wasn’t clear if he would pull through. In the midst of a morphine haze, he said, “I want to go home.” I assumed he meant back to his house, but he corrected me: “No, I want to be done living.”

Prompted by the Holy Spirit, I asked my dad if he felt confident about his eternal home. When he said no, amidst the bustling nurses and beeping machines, we prayed together—answering a petition I had been offering to God for more than 30 years.

As our parents approach the end of their lives, their spiritual and emotional needs are just as important as their physical needs. They may be bound up by fear and uncertainty about death yet unable to initiate a conversation about it. They may need help forgiving or finding closure in painful relationships. Asking direct questions such as “Is there anyone you need to forgive?” or “Is there anything you would like to talk about?” gives them permission to broach these topics. These holy moments also offer us the opportunity to express our gratitude and love for them.

New Normal

My dad did recover from surgery. He then faced three grueling months of rehab, frequently asking when he could go home. He hated being told what time to get up, what to eat, and when to go to bed. This loss of dignity made him question whether life was worth living. “The chance to shape one’s story is essential to sustaining meaning in life,” Atul Gawande wrote in Being Mortal. My father struggled to understand how—or if—he had any power to continue shaping his story.

Though my father had communicated that he did not want heroic measures to prolong his life, doctors continued to order tests and procedures until the last weeks of his life. As a result, he felt unheard and powerless. My sister and I had to advocate on his behalf, occasionally questioning or even declining the doctors’ suggestions.

Figuring out how to provide care for my father during this time pushed us all into unfamiliar emotional territory. He needed help with many basic activities that felt shameful to him. My sister and I were asked to provide the kind of care for him that we had never received from him. Dad was not an affectionate man. The first time I rubbed moisturizer on his dry feet, my stomach knotted up. I wanted to love him well, but such intimate contact reminded me of the times I longed to be comforted by him as a child. This left a bittersweet residue on my offering.

Finally Home

When I finally brought Dad home, a hospice team came and attempted to communicate what he could expect in the coming months. Dad was visibly confused when he was asked to sign papers promising that in the event of a respiratory emergency he would not call 911. While hospitals keep people alive, hospice offers them the best quality of life possible as they die with dignity. That first meeting with the hospice team sobered all of us.

One morning after Dad had been home for several months, his neighbor called me. My father confided in him that he thought death was near. This was contrary to what the hospice team assured us, in part because he was not manifesting end-of-life symptoms.

My husband and I made the trip to his home the next day. After helping my father get ready for bed, I held his hand and said, “You’ve been a good father. You’ve always provided for us and put our needs before yours. I’m so grateful for all you have done.” We prayed for him, and I kissed his forehead and said, “I’ll see you in the morning.” My husband slept downstairs on the couch by his side. Near dawn, his breathing changed and then simply stopped.

Though our relationship was far from perfect, I miss my dad terribly. No amount of preparation makes it easier for us to say goodbye to our parents. But by thoughtfully and prayerfully helping them navigate the end of life, we make it a bit easier for our mothers and fathers to find their way home.

Read more articles that highlight writing by Christian women at ChristianityToday.com/Women

Read These Next

Read These Next

2014 Editor's Pick: Church & Ministry3 Key Shifts that Could Change the Face of Women's MinistryI couldn't understand why so many young women in the church weren't attending women's ministry events. Then I started asking questions.

2014 Editor's Pick: Church & Ministry3 Key Shifts that Could Change the Face of Women's MinistryI couldn't understand why so many young women in the church weren't attending women's ministry events. Then I started asking questions.

Homepage

Homepage